If you don’t know, The Sealey Challenge begins today, a poetry reader’s challenge to read one book of poems a day.

The Sealey Challange was created by poet, Nicole Sealey, who decided to challenge herself by reading one book of poems each day, hoping to return to reading for pleasure while working a taxing day job. The rules of the challenge are simple! Form a reading list, read a book each day, and document/share your experience online – among a community of readers.

I’m so excited about this challenge and can relate to working a full-time job that drains me by the end of the day. I often feel guilty about not keeping up with my books or writing because of my job and it leaves me with a feeling of waste. I’m hoping to beat that feeling this August and also extend grace to myself. It’s a real privilege to be able to find time in your day to read, something I want to remind myself of.

If you need poetry suggestions, here are a few books off of my reading list for August 2022.

1. Swallowed Light by Micheal Wasson

I first encountered Micheal Wasson in the anthology, Shapes of Native Non-Fiction. After reading his poem, Self Portrait with Parts Missing and/or Smeared, I wanted to read more! Swallowed Light looks into the erasure of native people and the impact of colonialism, “exploring a legacy of erasure”.

2. Diaries of a Terrorist by Christopher Soto

I enjoyed reading the anthology Queer Poets of Color produced by Soto, and am even more excited for this collection of poems. Christopher Soto’s book of poems centers in on the theme of police violence, urging readers to think on the question of “who we call a terrorist and why?”.

3. My Baby First Birthday by Jenny Zhang

I heard Jenny Zhang read at a Tin House event a year or two ago and have been meaning to read more of her work. This book focuses on the idea of innocence in relation to women. The themes in this book scrutinize patriarchy, whiteness, capitalism, and the “violence and rescue of heroism”. (quote source)

4. Dictée by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

Dictée by Korean American artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha is an exploration of suffering through fragments of memory. “It is the story of several women: the Korean revolutionary Yu Guan Soon, Joan of Arc, Demeter and Persephone, Cha’s mother Hyung Soon Huo (a Korean born in Manchuria to first-generation Korean exiles), and Cha herself”. (quote source)

5. Maafa by Harmony Holiday

Harmony Holiday’s book, Maafa, which is also the Swahili word for great disaster or great trategy, specifically in reference to slavery is an entire poem on reparations and the body of a woman. “Maafa undoes the erasure of trauma and of black femininity”. (quote source)

6. The Trees Witness Everything by Victoria Chang

This book of Poems by Victoria Change includes a majority of poems written in the Waka form, a traditional form in Japanese poetry similar to the Haiku.

7. Girls that Never Die by Safia Elhillo

In Safia Elhio’s latest book, her writing shifts to a focus on the body, the body of a Muslim woman, and the shame and danger that can come with it.

8. Dream of the Divided Field by Yanyi

Following the theme of the body, Yani’s book of poems considers the act of leaving one’s self, like leaving a home – looking back at what still resonates within or what never was a part of that previous self.

9. My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long

Rachel Long’s collection of poems centers on the writer’s experience of womanhood following themes of “femininity, Black identity and familial shame”. (quote source)

10. Good Boys by Megan Fernandes

Megan Fernandes’ second book of poems contemplates the idea of being “good” in relation to submission and the dangers of considering submission to be a form of love.

11. Lotería Cards and Fortune Poems: A Book of Lives by Juan Felipe Herrera

Juan Felipe Herrera’s book of poems includes beautifully illustrated images of the 18th-century colonial game, Lotería, where Herrera interprets each card with a poem.

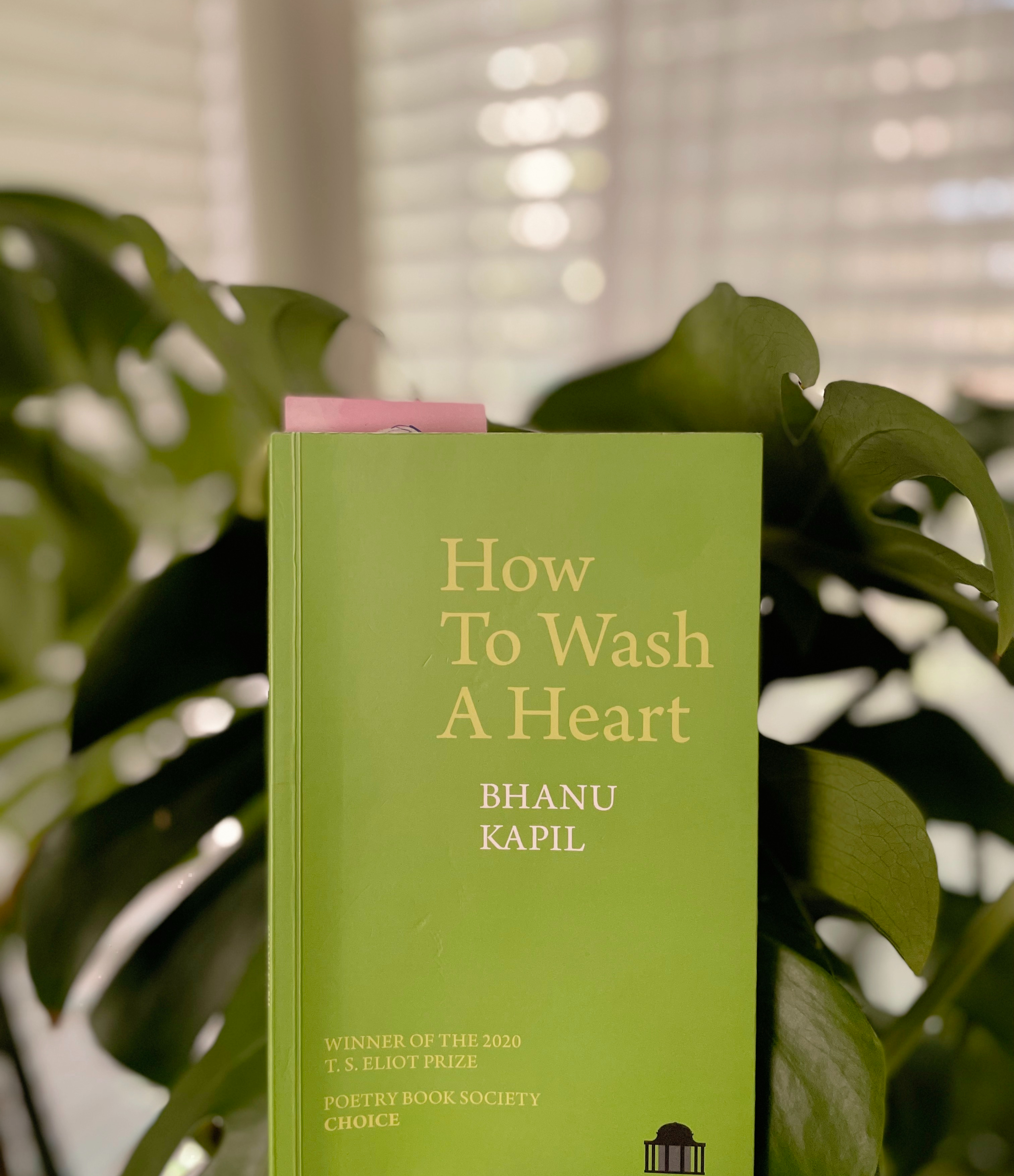

This past month I began reading Bhanu Kapil’s, How To Wash a Heart and could not stop crying. I tend to be a slow reader, so I read a few poems every night, and sometimes the poems I read in one night I re-read again and again. As a huge fan of Kapil’s work, I enjoy processing what Kapil’s mind offers [me] the reader.

This past month I began reading Bhanu Kapil’s, How To Wash a Heart and could not stop crying. I tend to be a slow reader, so I read a few poems every night, and sometimes the poems I read in one night I re-read again and again. As a huge fan of Kapil’s work, I enjoy processing what Kapil’s mind offers [me] the reader.